Honoring the Ordinary: Sharon Brown’s “Virginia: A Life,” at the Pattern Shop Studio

Sharon Brown’s “Virginia: A Life,” on display at the Pattern Shop Studio through December 2011, is the result of a 25-year-long, multi-layered project that has so far fostered 85 paintings, 37 of which are in this show. The inspiration for the project was two garbage bags of old photographs, letters and memorabilia that Sharon found in an alley when she and her neighbor were dumpster browsing. This is the first layer of the show’s meaning: all the paintings spring from images that were destined for oblivion. Were it not for a curious, even nosy, artist, they wouldn’t be in our visual vocabulary and we would be much the poorer for their absence.

It’s important up front to make a distinction between the historical artifacts that Sharon rescued from the trash and the art she has made out of them. Yes, there really was a historical Virginia, fragments of whose life survive in old snapshots, letters and memorabilia; and yes, these materials are of historical and cultural interest in their own right. But Sharon is an artist, not a cultural historian or biographer. The historical facts of the real Virginia and her life are about as important to this body of work as the facts about Dora Maar are to Picasso’s painting Dora Maar au Chat: in other words, not very. Artists are often inspired by “real” people and events, but they appropriate them to tell their own stories and express the kinds of truth that are particular to art, not to history or science. Although this show displays a few letters and artifacts to provide a context and setting for the paintings, remember that the “Virginia” you meet in this show is a person imagined by Sharon Brown, and the narrative the paintings create was constructed by Sharon to express her feelings and ideas and to stimulate yours.

Sharon’s interest in old photographs and letters has been lifelong. She grew up in a large family with dozens of photo albums, drawers full of old letters, and a habit of looking at them and reading them aloud at family gatherings. Even as a little girl, Sharon was curious about what life was like for her parents when they were “young and hot.” Her earliest drawings and the paper dolls she created for herself were of fashionably clothed and well-hatted women. Her aesthetic was formed by the black and white movies of the 1930’s and 40’s, which she still watches, and then by the movies, advertising, fashion and art of the 50’s. When a second cousin died, leaving Sharon her old photographs and letters, Sharon began to paint from them, as well as from other old family snapshots. It’s no wonder that a couple of years later, the trash bags full of Virginia’s old letters and snapshots were irresistible to her.

What drew Sharon to these materials was her interest in authentic voice (the letters), her interest in the period (1936-1944), and her fascination with old family snapshots. A sociology major in college, and the daughter, granddaughter and sister of psychiatrists, she has an eye for images that she can use to convey subtle psychological and social tensions. She sees the ways in which ordinary people reveal themselves, try to conceal themselves (often at the same time), and reflect culturally induced values. In the painting Pontiac, for example, we see a fur-clad Virginia standing proudly next to a splendid 1941 Pontiac Streamliner. Who among us doesn’t have such an image in that old shoe box in the closet–of ourselves or family members standing next to our first or most prized automobile? It’s an iconic American image, combining both personal and social pride. Virginia and Ed are proud of themselves for having acquired the trappings of an idyllic middle class life. She has her fur coat and fur hat and expensive handbag and shoes; he has his high status automobile and his Pretty Wife posing next to it like a model in Colliers Magazine or Life. The imagery says, “See? We’ve made it! We’re living the American Dream!” The dirt road on which the car rests and the scrawny trees in the background remind us that these people have clawed their way out of the Great Depression. The car itself points to a promising future of opulence and speed for everyone.

In painting after painting, Virginia and Ed are posing and showing off a new fur, a new hat, a new status symbol of some kind. You wouldn’t know that she was a secretary in an advertising agency, sending rent money back to her widowed mother in Denver or that he struggled with his confidence for years and scrimped to be able to afford even a long distance phone.

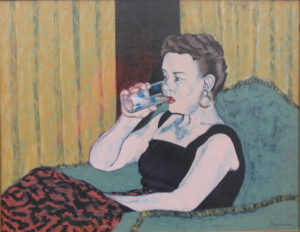

The original snapshots were meant to show their lives as they wanted to remember them and wanted others to see them. Sharon’s paintings, however, show more. She paints people in such a way that we see both who they are and who they would like others to believe they are at the same time. You see this very clearly in the smaller portraits of Virginia and her sister Mercedes, all of which are based on photo booth snapshots. These are not relaxed, happy faces. They’re tight, strained. Paint is both extra heavy on some parts of the face and removed on other parts, enabling the under-layers of paint to emerge like unconscious feelings. In Red Virginia, the emotions conveyed by the uneven layers of paint and the background are anger and disappointment; in Furred, we intuit some kind of sadness. In both, Sharon skillfully captures the mask Virginia is trying to project and, simultaneously, the face beneath the mask. Tensions– between brush strokes of various kinds, outer and under layers of paint, background and foreground colors, smooth and rough textures, light and dark, what the eyes say and what the mouth reveals–create the complexity and dynamism that make the images mysteriously compelling. Sharon’s striking portrait of Virginia’s sister, Mercedes, shows a smoother style befitting the subject’s more open face and temperament.

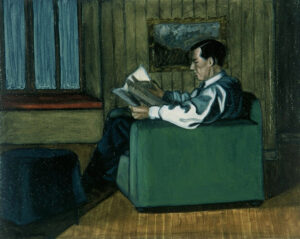

All of the paintings in the show repay close study. Most of the paintings on fiber board began with Milton Avery-like blocks or swaths of color, and you can see them bleeding through and influencing the figures on the surface. You can see Sharon’s deftness in so many of the fabrics she designs; her colorist instincts (remember–the snapshots are in black and white); her use of subtle washes to deepen shadows, darken corners, or weather bricks; and the psychological tensions she creates between Virginia and her father, or two visitors, or husbands and wives at a cocktail party.

Virginia: A Life is a labor of love now spanning almost 25 years and likely to go on until Sharon stops painting. Each painting tells a little story; the whole series conjures up a larger narrative about ordinary Americans in the 1930’s and 40’s trying to make it out of the Depression, through the war and into a burgeoning middle class. Sharon says that her primary impulse as a figurative artist has been to “honor the ordinary.” In rescuing a slice of someone’s life from the trash–a time when they were “young and hot” and in love–and turning what was discarded into something richly textured, beautiful and desirable, Sharon has given the “real” Virginia the glamorous life she apparently sought. In giving us her imagined Virginia, she has given us a character who is intriguing in her own right and reminiscent of the people who stare out at us from our dust-covered family photo albums. And in doing both, she has indeed brought honor to the ordinary.

- Rex Brown (Sharon’s husband)

Go back to Featured Series